http://www.hulu.com/watch/54909/a-celebration-of-black-history-james-meredith-remembers

Category Archives: Uncategorized

Conclusion

The Hattiesburg American was able to cover the article in a neutral light by reporting the facts of incidents without putting negative slander into their articles or headlines. The editors of the neutral articles only reported quotes from government officials who were stating the facts.

Articles that were considered positive biased encouraged Meredith’s ending of segregation. Positive articles did not focus on the negative surrounding Meredith; they spoke positively of Meredith’s attempting of entering the university. The articles that were concluded as being negative biased spoke slander words of Meredith. On October 1, 1962, an article in The Hattiesburg American blamed Meredith for the death of two people from the violent riot. Some negative articles would encourage the people who attempted to deny Meredith’s entrance.

Although other local papers such as Jackson Daily News and Meridian Star shown biased sides of the stories, such as Jackson Daily News headlines referencing the federal troops by calling them “government goonsqauds,” national weekly’s such as Time and Jet, were able to give a national perspective of the Meredith Crisis.

Jet provided commentary from the public and public officials. Jet was able to give commentaries from the general who shared different views of segregation.

Time provided commentary from public officials and conversations between Governor Barnett and a justice department aide. Time gave brief descriptions of Meredith’s legal battle and resistance of the south to integrate after Brown v. Board of Education.

Research Questions and Results

Articles used for this research were obtained from The Library of Hattiesburg, Petal, and Forrest County. Microform for Hattiesburg’s newspaper, The Hattiesburg American, and copies were reviewed. Stories relating to James Meredith’s entrance to Ole Miss were printed. Ten articles were obtained that were between published between May 31, 1961 and October 3, 1962.

1. Were the headlines biased against segregation, biased supporting segregation, or objective?

( 20% positive, 30% negative, 50% neutral)

2. Did the majority of the stories run on page one above or below the fold?

(100% on first page)

3. Was the tone the writer used positive, negative, or neutral?

(20% positive, 10% negative, 70% neutral)

4. Were the first three paragraphs of the article positive, negative, or neutral?

(40% negative, 60% neutral)

5. Did the photographs presented depict violence or non-violence?

(20% violence, 30% non-violent, 100% no photo)

Meredith Graduates from Ole Miss

January 30, 1963, Meredith announced at a Jackson news conference, “I have concluded that the ‘Negro’ should not return to the University of Mississippi. The prospects of him are too unpromising.” His statement had left many stunned. “However,” Meredith continued, “I have decided that I, J.H. Meredith, will register for the second semester at the University of Mississippi.”

At 5:12 P.M. on August 19, 1963, James Meredith received his Ole Miss diploma, a handshake, and “congratulations and good luck” from Chancellor Williams

October 1, 1962

October 1, 1962 marked the day that 114 years of segregation at The University of Mississippi had ended. James Meredith successfully registered for classes.

While attending classes he was accompanied by three U.S. marshals who tracked his every move.

That morning Meredith arrived at his nine o’clock American history class fourteen minutes late. Only nine of twelve students were present in the Graduate Building classroom. Meredith left his class an hour later with his escorts and returned to his dorm.

Later that day Meredith’s Spanish class was cancelled. Lingering tear gas forced the cancellation of his math class. Monday evening in his dorm room, Meredith ate dinner prepared by the army.

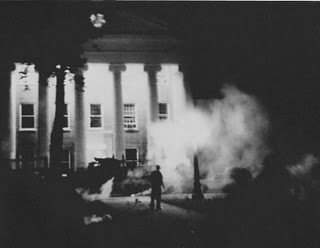

The Night of September 30, 1962

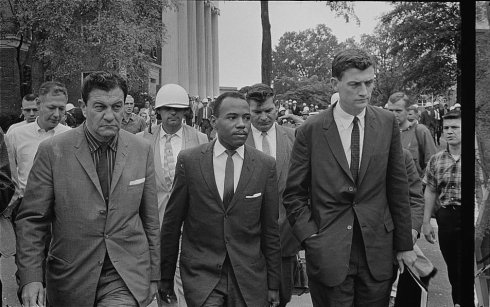

On Sunday, September 30, Meredith was flown into Oxford with 170 federal marshals. A mob of students, joined by outsiders, started to riot and began throwing bricks and setting fires. The highway patrol was withdrawn, not strengthened, and this was the green light for major violence.

The feds had turned the university’s administration building, the Lyceum, into the headquarters of the military’s operations. However, the federal law enforcement officers were not prepared. Police attempted to keep all students, faculty, employees and anyone else off campus; for a while they almost succeeded. During that time, journalists were entering the campus by finding their own ways in.

The mob was beginning to get out of control as hostile men from around the South entered university grounds as well. There was an estimated 2,500 men part of the mob. The mob was chanting, yelling, and firing bullets and pellets, throwing bottles, sticks and cans.

In Washington, President Kennedy prepared to go on national television to address the nation about his decision to use federal forces on the campus of Ole Miss, to announce that Meredith was in a dormitory, and to declare that he and Governor Barnett had made a peaceful solution. However, things on Ole Miss campus were only worsening.

Students were too busy rioting to listen to President Kennedy’s announcement. By nine o’clock that evening the first murdered occurred with Paul Guilhard, a reporter for Agence France Press. Guilhard was shot in the back with no witnesses.

Another fatality occurred with Oxford resident, Ray Gunter, who was a jukebox repairman. Gunter had come to campus out of curiosity. A stray .38 caliber shot Gunter in the forehead.

The night resulted with two deaths and one hundred and 60 marshals injured. Two hundred rioters were arrested, less than one-sixth of whom were from Ole Miss.

Governor Barnett vs. Meredith

It seemed that the state of Mississippi was split up by two different kinds of racists, the mild racists such as John Coleman and rabid racists such as Governor Ross Barnett. Supporters of Ross Barnett were equally racist judges who upheld the right of the University and denied Meredith twice.

February 4, 1961, after Meredith first attempt to enter the university was unsucessful, an integration scare swept over the state of Mississippi. Fearing that there would be integration happening at the University of Mississippi, Governor Ross Barnett had sent eight state troopers to the Ole Miss campus. When Governor Barnett was questioned, he refused to comment. The attorney general’s office said it did not know what was happening at Ole Miss and the patrolmen that were sent to campus claimed they were only doing a civil defense exercise and/or registering for graduate classes.

After the Court of Appeals approved of Meredith’s entrance to Ole Miss, Governor Barnett tried passing a law against Meredith that “prohibited any person who was convicted of a state crime from admission to a state school,” because Meredith had been convicted of false voter registration previously.

On September 13, Governor Barnett was determined to stop the court’s decision of integrating the University of Mississippi. Governor Barnett spoke on live radio and television stating that the people of Mississippi had a choice: either they submitted to the tyranny of the federal government or they acted like men and resisted. Barnett explained, “Mississippi, as a Sovereign State, has the right under the federal Constitution to determine for itself what the federal Constitution has reserved to it.”

The Kennedy’s continued to fight with an ignorant Governor Barnett over the registration of Meredith until Meredith was successfully entered at the university.

Timeline of James Meredith

- Jan. 26, 1961, Ole Miss receives letter from Meredith requesting application

- Jan. 31, Meredith mails in application stating he is an African-American

- Feb. 4, Meredith receives telegram denying his registration

- May 31, Meredith began (NAACP) legal battle against Ole Miss

- Feb. 3, 1962, Judge Sidney Mize ruled that race was not cause of rejection

- April 20, Court of Appeals hears case

- June 25, Judge Wisdom ruled that Ole Miss denied him because of race

- Sept. 20, Meredith denied at Oxford registration

- Sept. 30, Meredith is flown into Oxford with 170 marshals. ( The following night a violent riot breaks out resulting in two deaths)

- Oct. 1, Meredith successfully registers for classes

- August 19, 1963. Meredith recieves his Ole Miss diploma

Literature Review

- James Meredith was born June 25, 1933 in Kosciusko, Mississippi

- Meredith says he always felt conscious of his skin color growing up in Mississippi.

- “Separation dominated my childhood completely,” Meredith quoted once.

- After graduating from Gibbs High School in June 1951, Meredith wanted to go to college but could not afford it. He moved to Detroit, MI where his stepbrother and stepsister lived and followed their footsteps and joined the military.

- Meredith served as staff sergeant in an American airbase outside of Tokyo, Japan

- Coverage of the Little Rock Crisis was widely covered in Japan

- Sept. 1957 Meredith spoke with Japanese schoolboy. The Japanese boy told Meredith he did not know why anyone would go back to Mississippi

- This incident along with the Little Rock Crisis influenced Meredith

- Meredith was dishonorably discharged in 1960 and attended the all black Jackson State College to complete a bachelor’s degree in political science

- Meredith wanted to further his education at a school he felt was the best school in Mississippi, the University of Mississippi

Mississippi papers such the Jackson Daily News and the Meridian Star showed signs of being negative biased as well. During the Meredith Crisis, Jackson Daily News headlines referenced the federal troops by calling them “government goonsqauds.” The Meridian Star had headlines reading “Negro Attends Ole Miss at Cost of Two Lives.”

National magazines such as Jet and Time, covered many of their articles through a neutral tone and wereable to give a national perspective.

More than half of Jet’s articles contained commentary from the general public and public officials. Jet also contained comments from members of the public that shared different opinions on segregation. However, some of Jet’s articles seemed to lean towards a positive biased of desegregation. For example, one of Jet’s editorial pieces urged President Kennedy to arrest Governor Barnett. Jet was also advertising ads urging readers to donate to NAACP.

Time covered articles that consisted of commentary from public officials. ( 13 out of 19 sources were quoted from an official/ 68%) Time was able to provide commentary from several of Meredith’s failed attempts while trying to enter the university. The article also contained a conversation between Governor Barnett and a justice department aide.

Doar: Do you refuse to permit us to come in the door?

Barnett: Yes, sir

Doar: All right, Thank you.

Barnett: I do that politely.

Doar: Thank you. We leave politely

Time was able to give brief descriptions of Meredith’s seventeen-month legal battle for admission against Ole Miss and acknowledged the southern resistance to Brown v. Board of Education.